Play

To engage in a physical or cognitive activity for enjoyment. Play is common across human societies and even among animals—just think of kittens playing together!

While the ease of play is often associated with the innocence of childhood, it undoubtedly fills everyone with wonder, and artists are no exception. Calder’s Circus comes to mind, along with his mobiles that defy the laws of gravity with their metal rods and colourful shapes that hang like tight rope walkers!

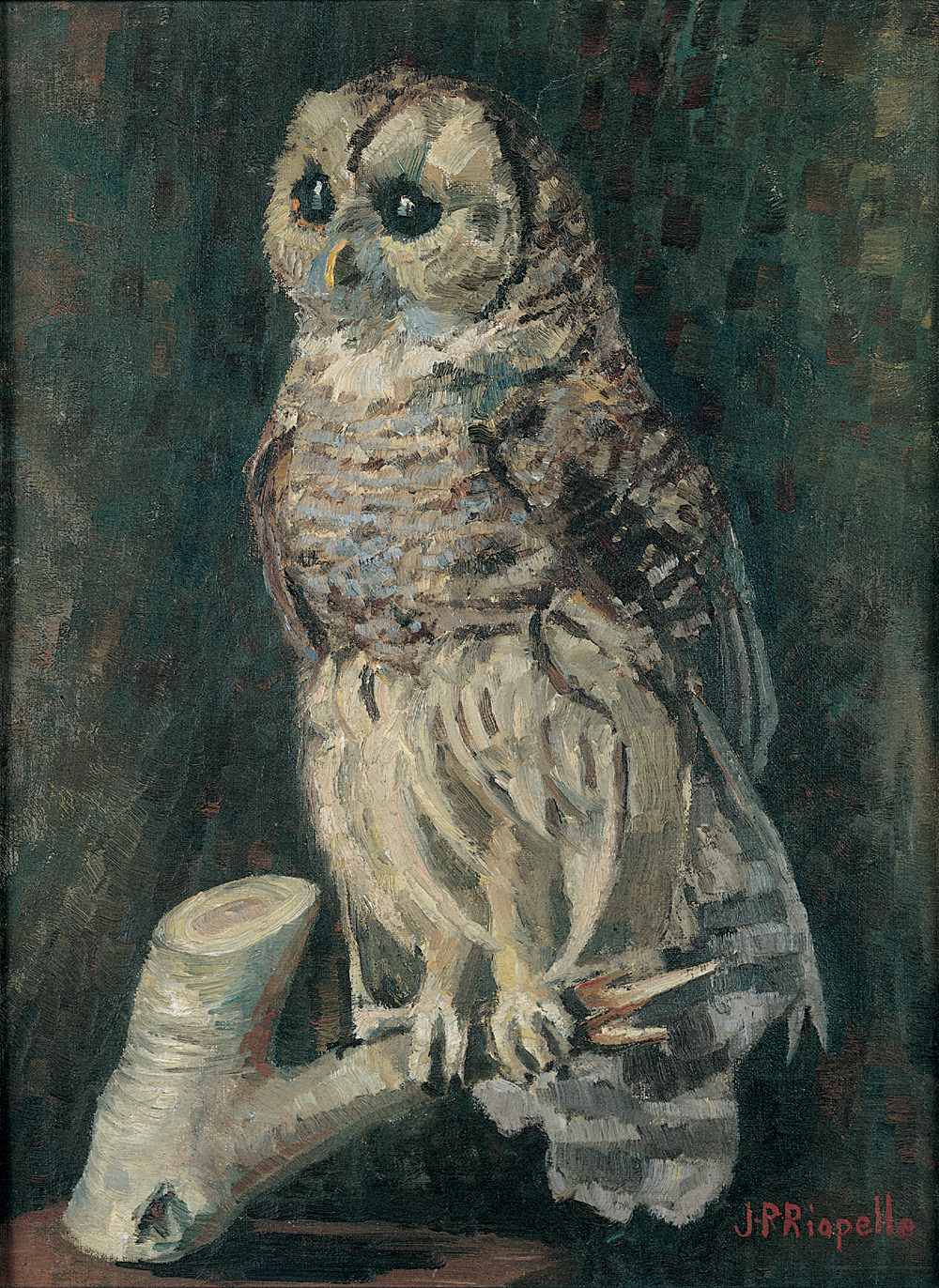

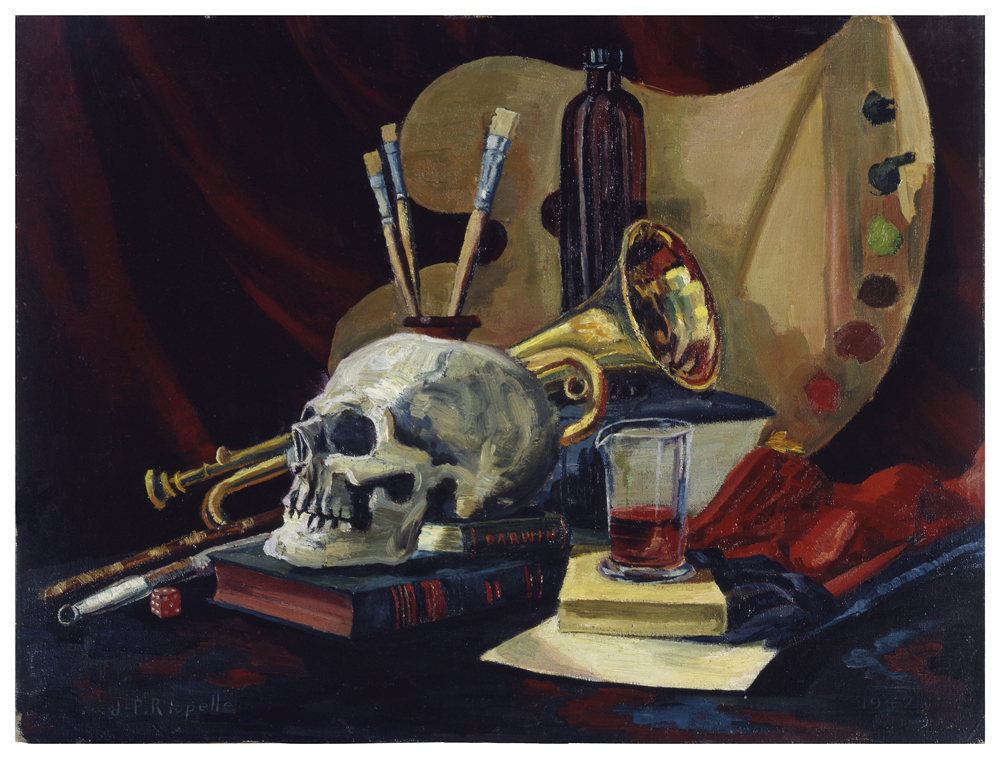

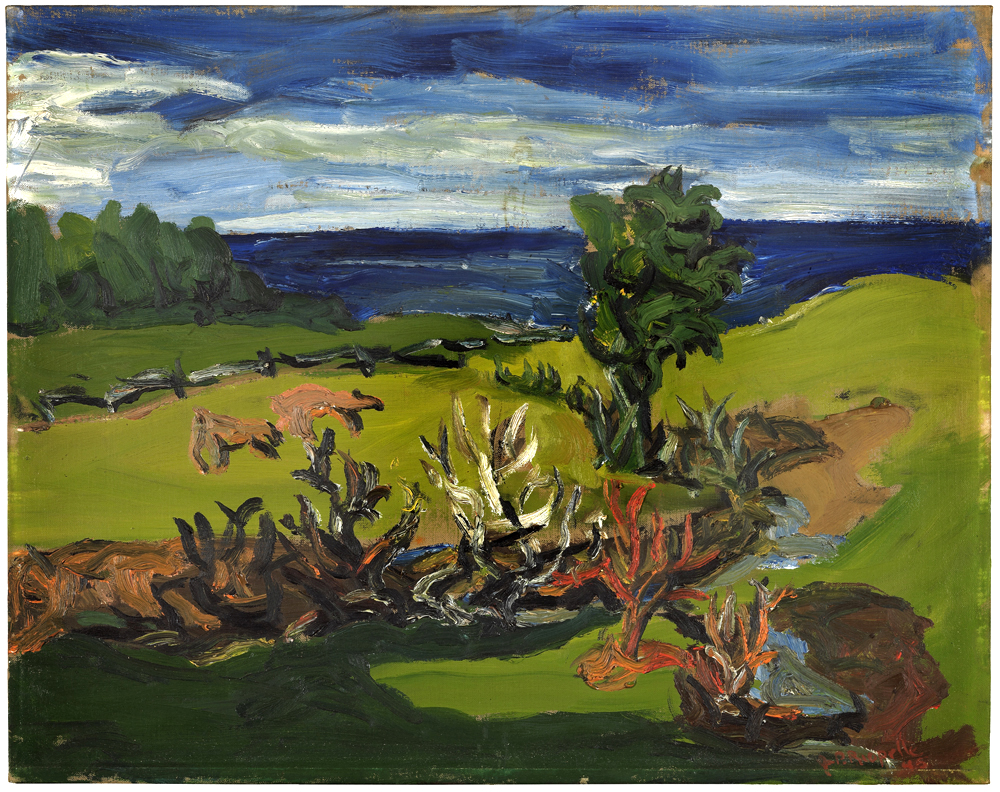

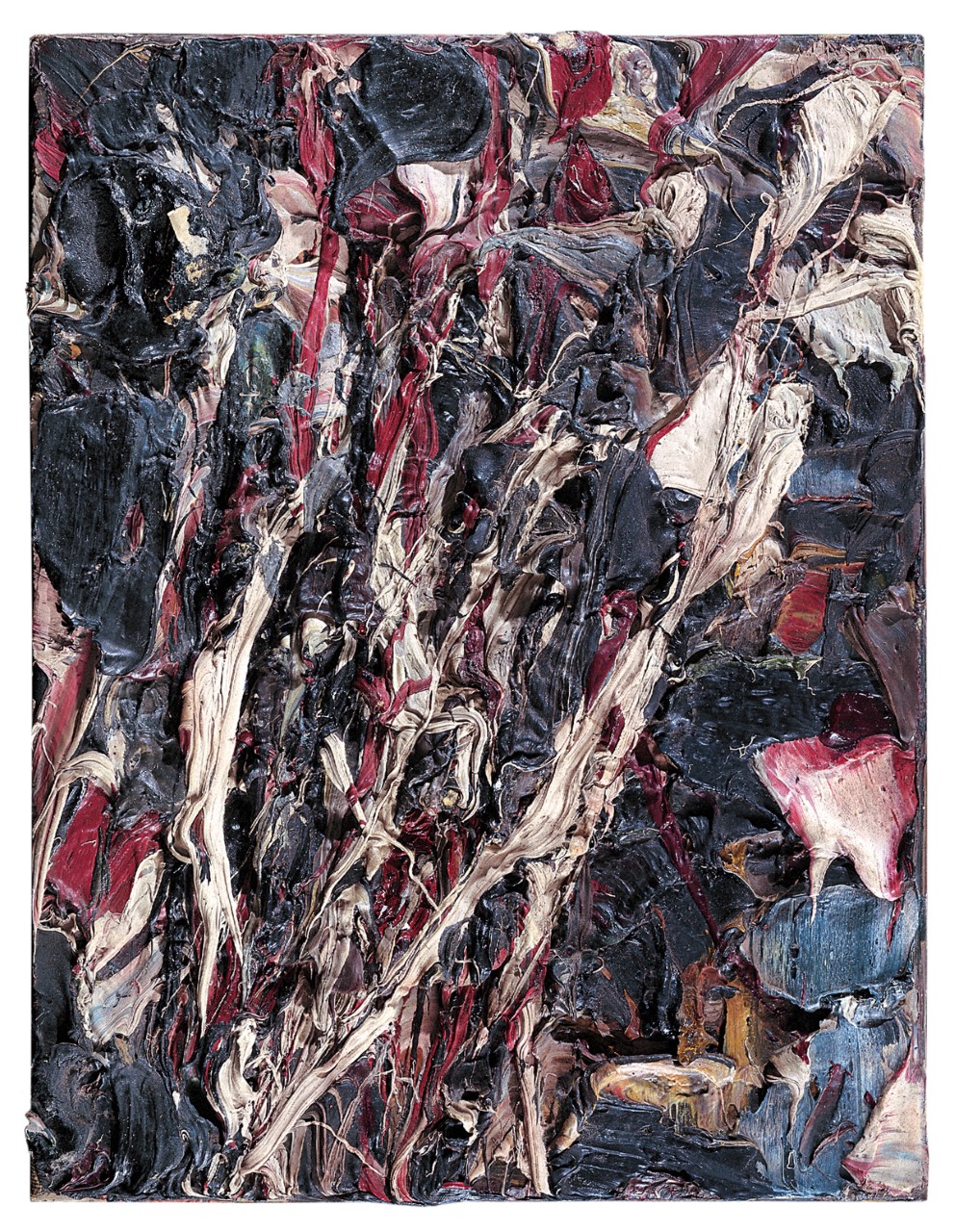

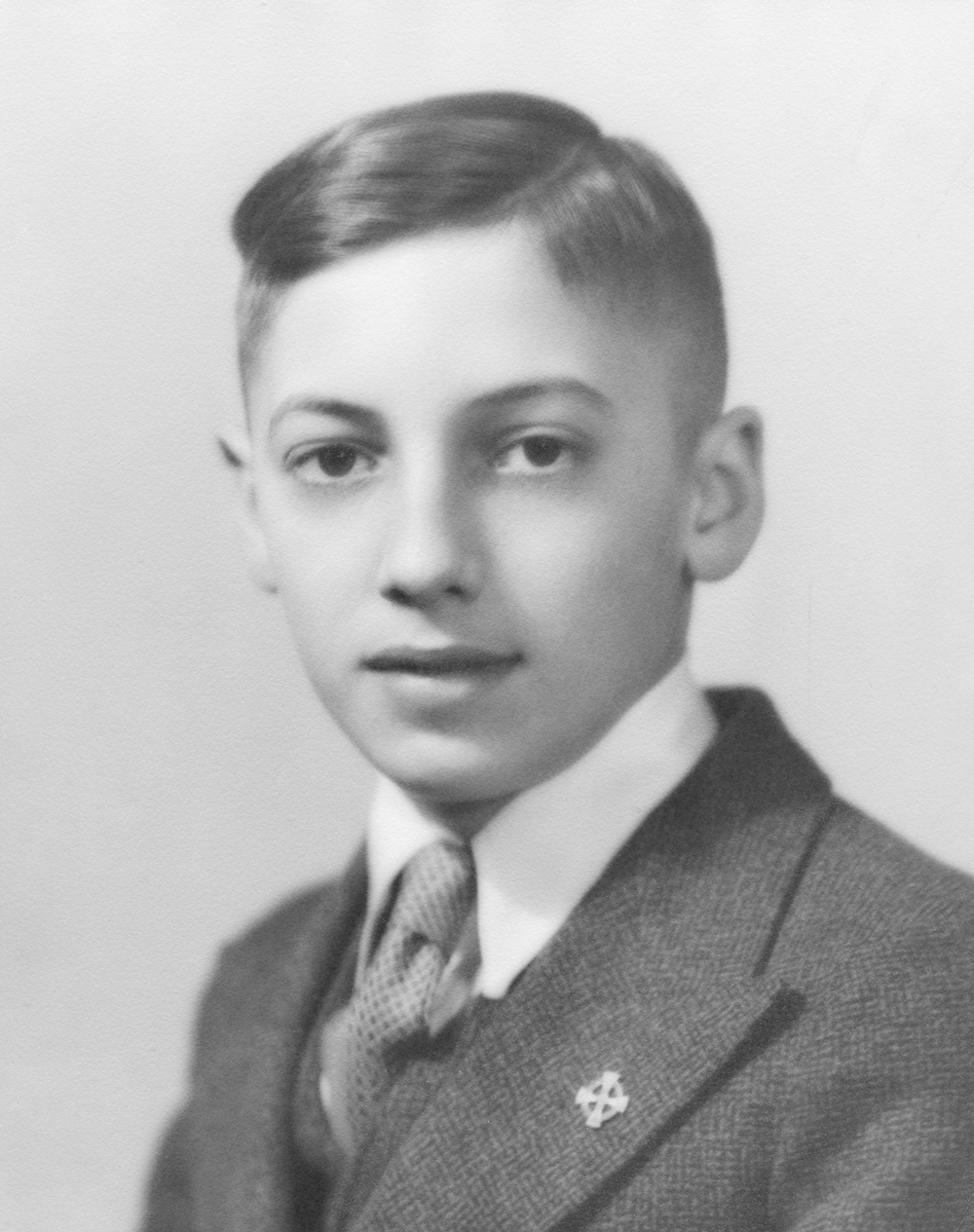

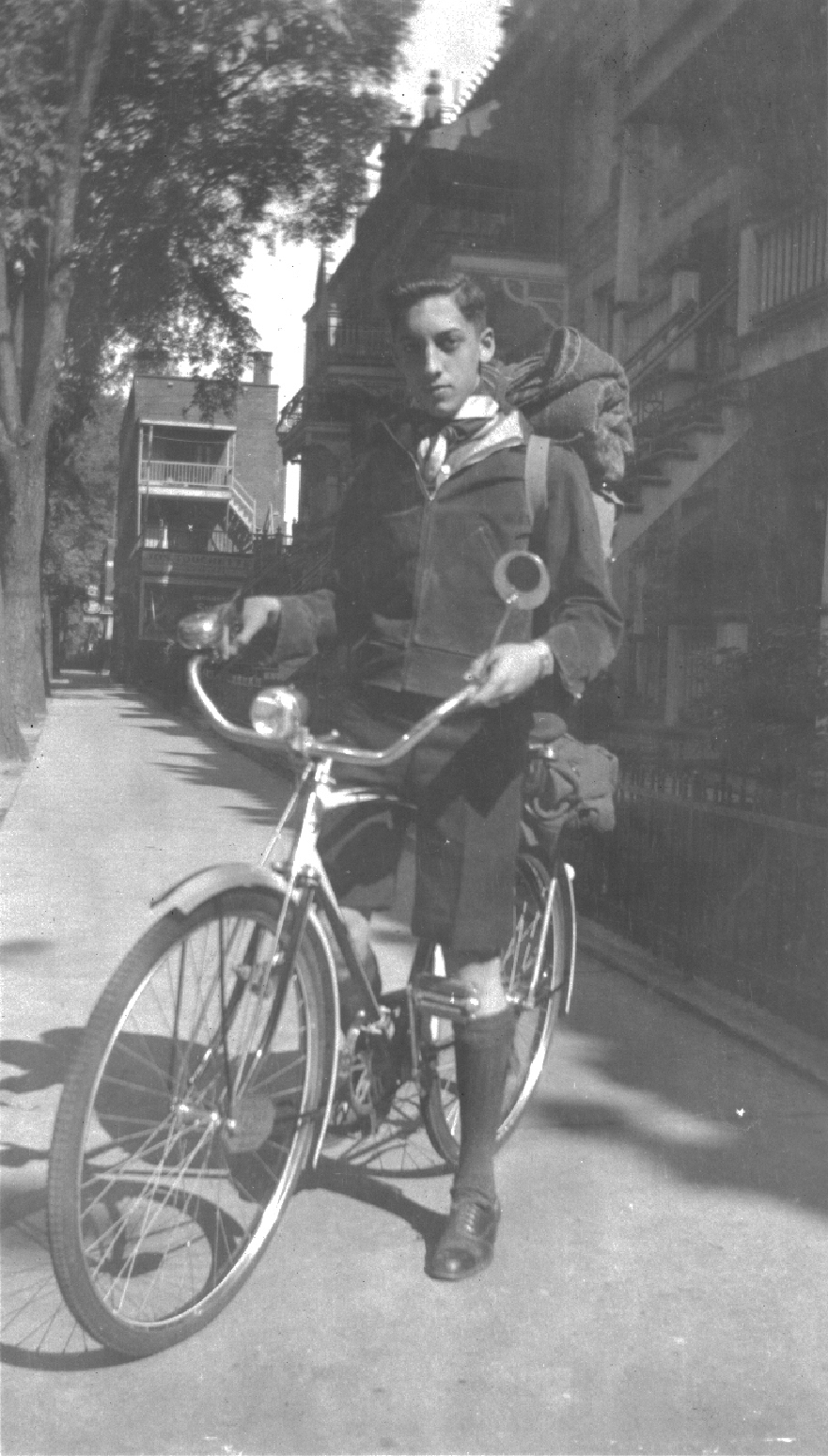

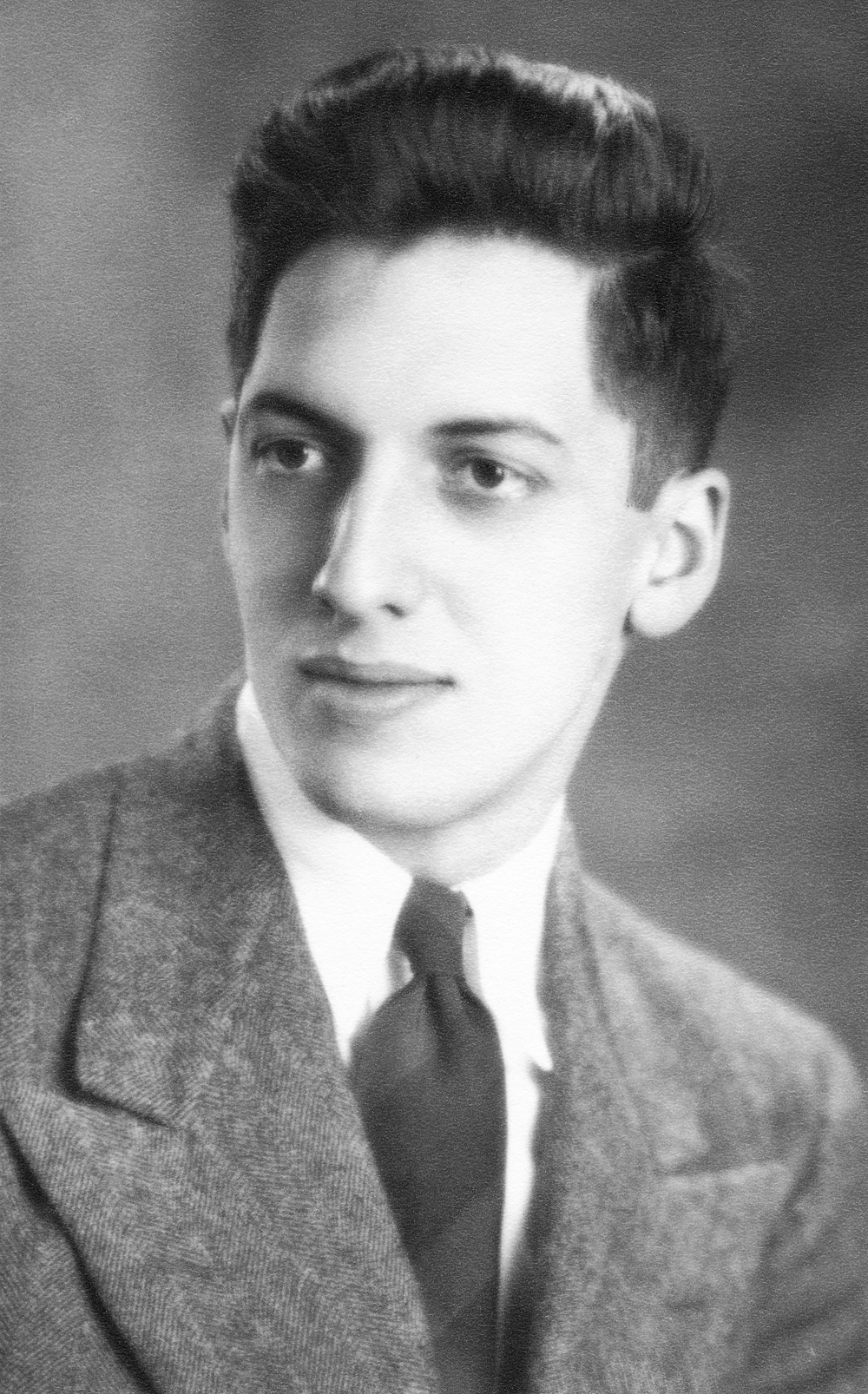

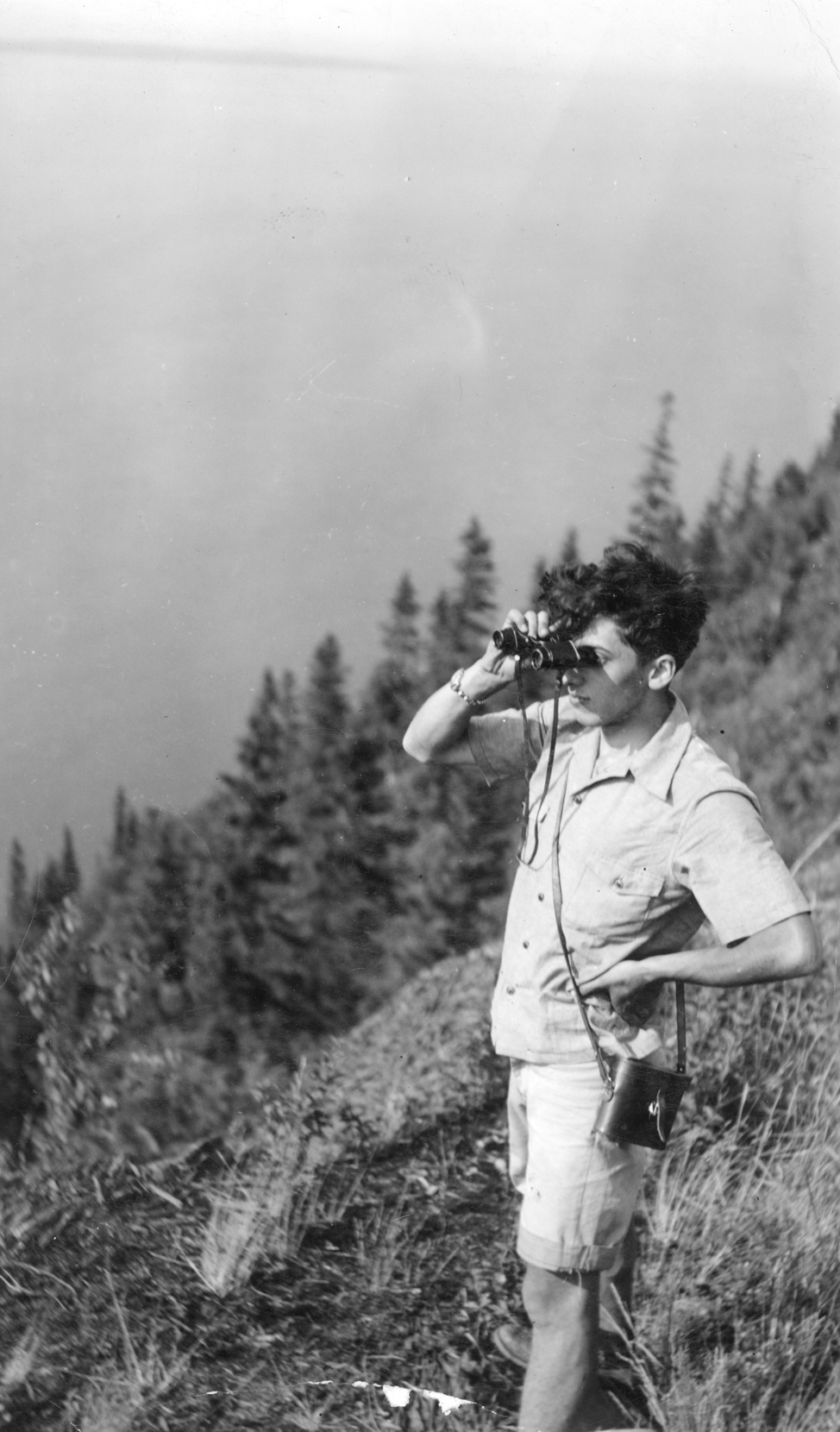

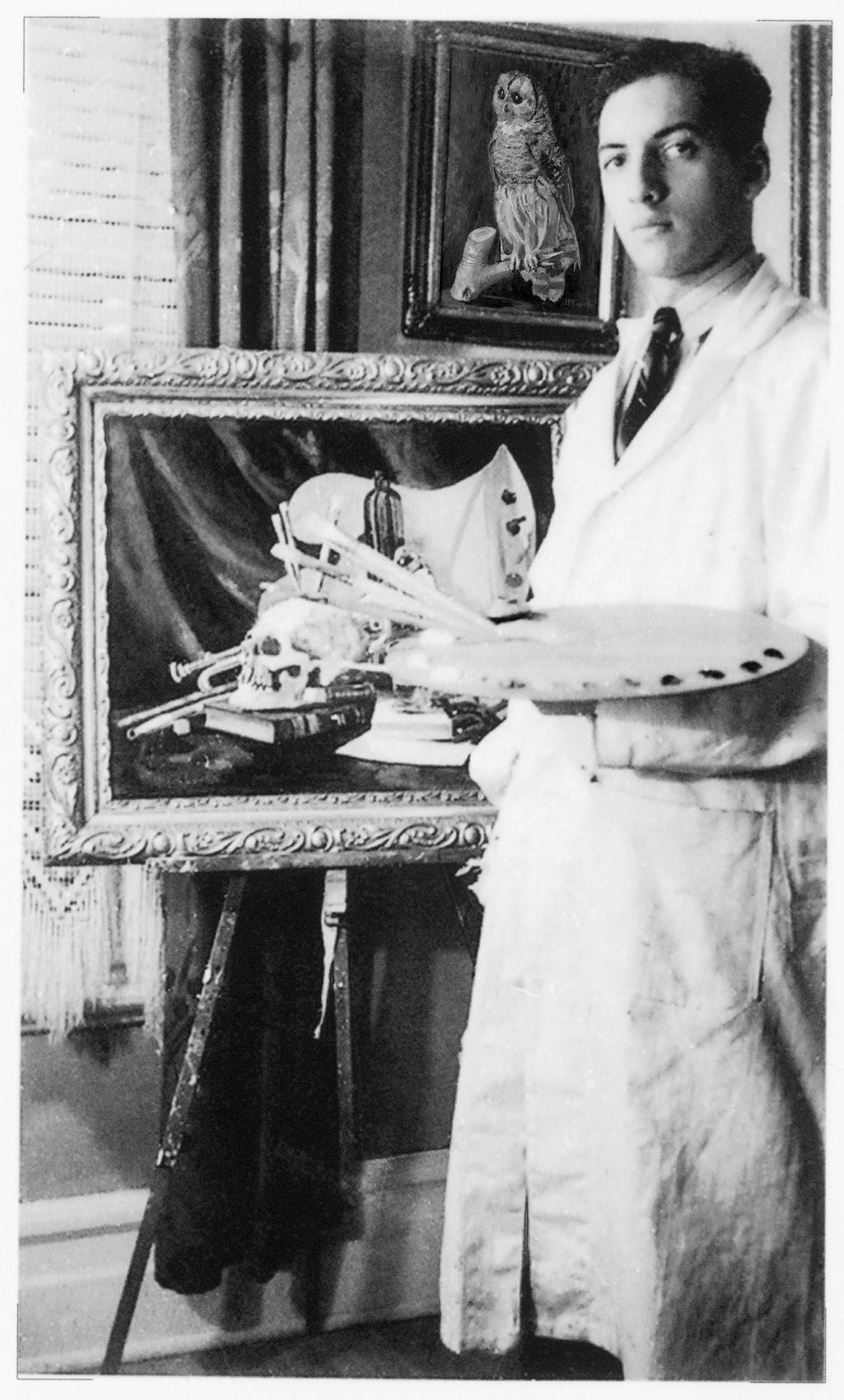

Jean Paul Riopelle has always blurred the boundaries between play and art. The artist loved clowning around. His friends fondly remember the time he built tiny chairs out of champagne corks, or the time he crawled through a dog door to impress a famous art dealer. Play was at the heart of Jean Paul’s storytelling: he had the gift of telling fantastical stories that he’d claim were true, or share true stories that were just as astonishing—like his time like his time stealing roosters from church steeples!

Jean Paul’s body of work lives and breathes play. He created a series of paintings featuring string games known as ajaraaq in Inuktitut, a traditional game that portrays Inuit life stories and legends. His fascination with them first came from a book, and he was already having fun playing these games with his daughters when they were young.

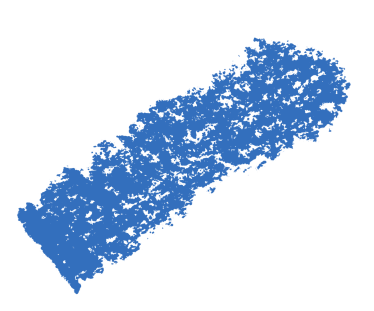

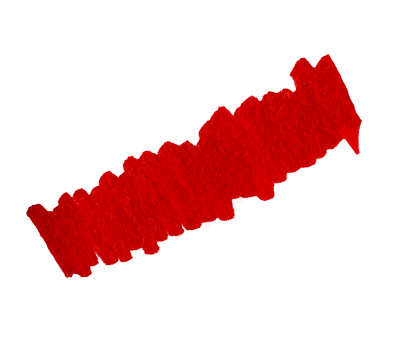

Jean Paul also played with sculpture. For example, his piece Le Chien-Isabelle, 1969-1970 is a stuffed dog that he received as a gift and cast in bronze! And then there’s La Joute, the monumental fountain sculpture located in Montréal’s International District. It was created as a nod to capture the flag, which was a very popular team sport in schoolyards at the time. It comes as no surprise that Jean Paul’s interests brought him to the surrealists, French poets and artists who placed imagination at the heart of their creative processes by creating games such as cadavres exquis.

Read more

Jean Paul Riopelle, La Joute, bronze, lost wax, 3,8 m (height) x 12,40 m (diameter) — approximate dimensions (1969-1970); cast around 1974 © Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle / Copyright Visuals Arts – CARCC (2023)

“ It’s a given. Whenever you spoke with Riopelle, you’d end up talking far more about boxing, hockey, car racing, the circus, etc., than painting. ”

F.-M. Gagnon. « Le cirque de Riopelle », Vie des arts, vol. 40, n° 165, 1996, p. 54-55.

Browse the works in the collection Play

Discover photos

Youth Project

Youth Project

Teen Project

Teen Project

Project for Everyone

Project for Everyone